Migration

Migration is the seasonal movement of animals from one habitat to another. Animals migrate between their wintering and breeding habitats. Some creatures that you would recognize that migrate are: whales, fish, butterflies, turtles, and of course birds. Some animals travel incredible distances on these annual journeys. The longest migration of any known animal is that of the Arctic Tern, which travels 15,000 miles from the North Pole to the South Pole and back again each year!

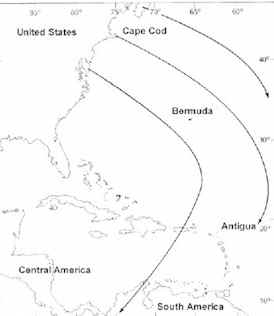

Migrating birds follow established migratory routes. Migration in North America is essentially north-south along four major routes known as "flyways:" Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic. Many birds migrate between North and South America and are referred to as Neo-tropical migrants (Neo = new + tropical). Most of these birds migrate 500 miles non-stop over the Gulf of Mexico. Other birds island hop down the eastern coast of the U.S. (see maps below). Upon arrival in southern wintering grounds, birds have been described as nothing more than "feathered skeletons" having depleted much of their fat and muscle reserves.Up to 12 million neotropical migrant birds have passed over Cape Cod in one night, embarking on a non-stop journey of 80 to 90 hours. Radar stations in Bermuda and Antigua pick up waves of approaching migrants.

Why do birds Migrate?

- Seasonal cycles of climate or insect abundance attract corresponding cycles of breeding, flocking, and migratory relocation.

- Migration benefits are species or population specific and include the need to escape inhospitable climates, probable starvation, social dominance, shortage of nest/roost sites, or competition for food.

- Another way to view the same ecological forces is that migrants aggressively exploit temporarily available opportunities.

- Traveling to different habitats enables birds to find plenty of food throughout the year. For example, in the winter, when food sources are limited in northern areas, waterfowl such as geese fly south to areas that have mild weather and abundant food.

How do birds navigate over such large tracts of land and ocean?

It has been demonstrated that birds rely on several different cues – visual landmarks, geomagnetic field, solar compass, skylight polarization pattern/stars, and olfaction - for their orientation and navigation across vast stretches of land. See below for research that demonstrated these phenomena.

Schlicte and Schmidt-Koenig (1971) fitted well-trained homing pigeons with frosted contact lenses that limited image formation beyond 3 meters. The blind birds flew over 170 km directly back to their lofts. Of course some crashed into the loft and some missed the loft altogether!

Emlen and Penny (1964) took Adelie Penguins from their coastal breeding rookeries to interior Antarctica and released them. On cloudy days the penguins wandered about randomly. -However, when the sun was shining they headed north-northeast towards the coast, compensating for the sun’s counterclockwise movement in the Southern Hemisphere by correcting their orientation 15 degrees per hour clockwise relative to the sun’s position…By the way the sun changes continuously by 15 degrees per hour.

Franz and Eleanore Sauer (1957) demonstrated the use of stars for navigation by birds. By caging Garden Warblers in a Planetarium, the Sauers showed birds oriented north in the "spring" and south in the "fall" under simulated night skies. When they turned off the stars the birds became disoriented. When they rotated the north-south axis of the planetarium 180o the warblers also reversed their compass headings.

Merkel and Wiltschko (1965) showed European Robins could orient in solid steel cages without celestial cues. They also demonstrated that the robins reversed their orientation when the magnetic field imposed on the cage was reversed.

Continuing the magnetism work Keeton (1971) demonstrated that free flying homing pigeons wearing bar magnets often did not orient properly on cloudy days vs. control pigeons wearing brass bars. Keeton concluded that the pigeons use the sun preferentially to the earth’s magnetic field on sunny days.

Finally, Walcott and Green (1974) fitted homing pigeons with electric caps that produced a magnetic field through the bird’s head. Under overcast skies, reversing the field’s direction by reversing the current in the cap caused free-flying pigeons to fly in the direction opposite their original course.